The Unwritten Half of Scientific Research

Dec 15, 2025

Modern ML papers are looking more polished than ever, yet feel hard to read and harder to build upon. This blog is about the unwritten half of scientific research: the tacit decisions and details that never make it into the PDF. At the end, I also point to what a better publishable artifact could look like.

Scapegoat

It was November 2025, and I was burnt out from the ICLR review cycle. I kept seeing the same patterns across X. Authors felt the reviews were low effort, and reviewers felt they were drowning in lousy submissions. I was quick to diagnose this issue as stemming from relentless LLM usage and ranted on X (which wasn’t a particularly wise judgement looking back).

I frequently saw posts like this one. This was my first ICLR submission … and I must say that I’m not impressed. There may not be a second.

Or consider this infamous case of a reviewer who always gave 40 verbose Weaknesses and Questions to all the papers they reviewed, then miraculously got convinced by the authors’ rebuttal and increased the score to 10, after they were flamed publicly and following the public information leak of OpenReview. I could list hundreds of raging posts, or argue that conferences should allocate substantial screening resources before papers hit the reviewers. However, that would deviate from the goal of this blog. I am not trying to paint someone, or some technology, as the villain. I want to figure out what drives such experiences.

If someone reads this years later, they might wonder what the situation was in 2025. Here is the feeling many people share today: manuscripts look more polished than ever, but they feel harder to trust and understand. Reviews also started to feel generic, and default to “dutifully” highlighting missing baselines or incremental novelty. People blame LLMs for this slop, both on the authors’ side and the reviewers’ side. And sometimes they are right.

But the deeper issue existed even before LLMs. Every paper has a core idea, and then there are pages of text that try to make it feel like a proper paper. A lot of key details live outside these PDFs, in the author’s head, in private code repositories, in Slack messages, or in “we tried a bunch of stuff” that never really got recorded and made it to the final manuscript. The juicy part of research is often not even in the final 10-page PDF. It lives in unwritten context.

This is what this blog will be about: tacit knowledge, and the prosaic fluff that surrounds good ideas.

Why 2025 feels like the tipping point?

Why have LLMs pushed things over the edge? Simple. LLMs speed up everything, and that creates volume. Flaws become glaring flaws once there is enough volume.

LLMs help you code faster, which means you can run more experiments. Instead of setting up baseline comparisons, researchers can move on to the next idea for the next conference. LLMs also help generate decent sounding paper text really quickly. Not just editing or improving structure, but filling in the parts that make a paper sound like a paper: the introduction, related work, conclusion, and the experimental takeaways summarized. The contributions are already clear to the authors. LLMs generate the surrounding text to make it reviewer friendly, so the paper does not raise red flags or deviate too much from what a good paper is supposed to look like. Authors can then focus on the parts that feel more “core”, like the abstract, the method, and the results.

“Writing good papers is an essential survival skill of an academic (kind of like making fire for a caveman). In particular, it is very important to realize that papers are a specific thing: they look a certain way, they flow a certain way, they have a certain structure, language, and statistics that the other academics expect” — Karpathy mentioned in blog. He also recalls “being impressed with Fei-Fei (my adviser) once during a reviewing session. I had a stack of 4 papers I had reviewed over the last several hours and she picked them up, flipped through each one for 10 seconds, and said one of them was good and the other three bad”. That blog was written before the GPT era. What made a paper “look publishable” then is starting to lose its meaning now. Paper-like writing used to be a signal of effort, however weak it was. Now it is cheap. When it is cheap, it stops helping reviewers separate careful work from rushed work.

The PDF problem and the Reproducibility problem

I think two things are broken in ML publishing.

First, as discussed, is writing. The 10-page PDF has become ubiquitous. The real contribution is often small and sharp, but it gets wrapped in a lot of prose whose job is to look like a proper paper.

Second, I will talk about this in a bit, is reproducibility. Even when you understand the main idea, it can still be hard to reproduce the results. This becomes a real problem the moment you want to build on the work. (There seems to be some confusion between replication and reproducibility. ReScience C explains this distinction cleanly. Reproducibility means rerunning the same computation and getting the same result. Replication means independently re-implementing and still getting the claim)

These two problems connect. A lot of papers are not written to be self-sufficient. They assume the reader already knows the task setup, the assumptions, the data-cleaning choices, and the eval protocols. This is why I believe that stories are worth bringing up.

Before you judge my lineup, this is just my desk setup, and my bookshelves at home are better, I promise.

Stories are not science, and they are certainly not rigorous, “suffering” from a wide gamut of interpretability. But they do one thing really really well: they are self-contained. You can start reading Lord of the Rings at page one. You do not need hidden context from the author to follow what is happening. There is no implied information, and that’s why anyone can start reading. That is why an 18-year-old and a 50-year-old can both read it, follow it, and even come up with what a sequel might look like. However, research papers often fail at this. The experienced reader can skim and still get it. The newer reader gets stuck because the paper assumes implied information and implicit steps.

After that, it is hard not to ask what a paper is supposed to do for a reader.I wonder what is the point of the present day 10-page PDFs if the new reader would anyway use ChatGPT to talk to that PDF and have a better understanding in 10 minutes than they were to get by hours of perusing? There are websites such as AlphaXiv that help researchers cut through context clutter and get right into what a paper does and how it does that. If you feel like you lack background knowledge, you can even ask ChatGPT to produce a reading list to get you up to speed and that is something that I use a lot. Papers that become helpful in this category are mostly studies. They do not have to bear the weight of novelty or the prosaic necessities of a “good paper”. They are optimized for human reading. I also like JMLR and TMLR papers for this reason. Many readers already use chat tools to talk to PDFs anyway, and these tools will only get better. I would prefer more distill style writing and interactive formatting. So what is the 10-page PDF for, if it is not self-contained and hard to parse?

To be clear, I do not blame PhD researchers who are burdened by the need to publish. I want to understand what drives these practices. What are the incentives, spelled out, that push writing in the wrong direction?

Incentives that aggravate the PDF problem and the Reproducibility Problem

Optimised for Peer Review A paper is written for reviewers as much as for anyone else. Reviewers decide whether it gets accepted. MIT SLOAN’s study Does Peer Review Penalize Scientific Risk Taking? found out that grants in the highest-risk decile are renewed at meaningfully lower rates than those in the lowest-risk decile. The risk penalty is larger for more novel work and for new and early-stage investigators, while the elites (National Academy members) face a smaller penalty. When evaluators have weaker priors about you or the area, they demand safer signals, which is our setting in double-blind peer review. (Granted that grant panels and peer reviewers are different, but the incentive is similar)

No reward for clarity There is little direct reward for producing work that is optimized for human understanding, especially for humans of different backgrounds. Research is not organized like coursework. A lot of mental horsepower goes into inflating ideas into publishable hunks of 10-page PDFs.

I remember in my senior secondary, when I was preparing for my JEE exam, how well organized everything was. Mathematics, organic, inorganic, physical chemistry, and physics were packaged into coaching modules, test series, and notes that compressed two years of knowledge very well. All because of incentive. It was in the best interest of the publisher to organise text for maximal understanding, and have their pupil succeed in an exam of 1.5 million candidates and 1% selection rate.

You know what bothers me even more than unorganization? Unwarranted verbosity. People flexing a about the word count in their theses. Once again, as I’d like it to be known, the real problem is not just that papers have more content than necessary. It is that papers hide the information you need to trust them and build on them.

A random post I found on X. Representative of what I am trying to convey with the above para.

A random post I found on X. Representative of what I am trying to convey with the above para.

On the bright side, I expect we will see this writing crisis abate soon. There is a funny side effect to LLMs democratising access to polished text. Papers have been written lousily and low-effort, polished text — just that with LLMs, anything with an iota of generic sounding BS gets accused of as GPT generated. When it gets so easy for everyone to cook up a word salad, and the ability to make one is no longer an indicator of articulation prowess or intellect, people realise this and revert back to using their own style. I’d like to believe that papers would receive the same treatment and improve.

We are, however, reaching another mountain which is more strenuous. Even the most powerful chatbots won’t be able to help if they cannot see how a paper came about its results!

Reproducibility is optional While working on my own research experiments, I often get stuck trying to reproduce results. Responses from authors along the lines of “we used GPT 4 turbo for LLM-as-a-judge evaluations” and it so happens that OpenAI discontinued this model through its API so the past evaluations are of no good use. How convenient. Or “we used a second stage of reranking to get better results” which is nowhere to be seen in the manuscript or the source code but I luckily stumbled upon a GitHub issue that mentions how this is common practice with such methods. Really! Who would’ve guessed, right? More common are papers with incomplete or bug-ridden code, parts commented out, and undefined hyperparameters, or no code available whatsoever.

Tacit knowledge is often withheld to monopolize research. If you can prevent people from building on top of your work, while still having this work out there in public so colleagues appreciate your contributions, while you squeeze out publications on top of your past work, then congratulations! You’ve achieved what is now common practice. You see what is happening? This tacit information is becoming a moat. (I do acknowledge it is not always intentional)

Someone in a Hacker News article rightly pointed out that academic papers are like publishing software into a blockchain (not source but binaries, meaning PDFs full of shortcuts): you do not want people to easily find bugs and contribute fixes, so you handwave a lot so that no one can reproduce your exact thing.

The real bottleneck is not reading the PDF. It is everything the PDF cannot carry: the exact data path, the environment, the code, the seeds, et al. If we want papers to be trustworthy and buildable, the paper cannot just describe computation. To this end, I define the unwritten half of scientific research as the information that is not present in the paper but is required to build on top of it.

The hanging question is in figuring out how to publish that missing half. Following is the first thing I’ve seen that makes the unwritten half of scientific research publishable.

NeuroLibre

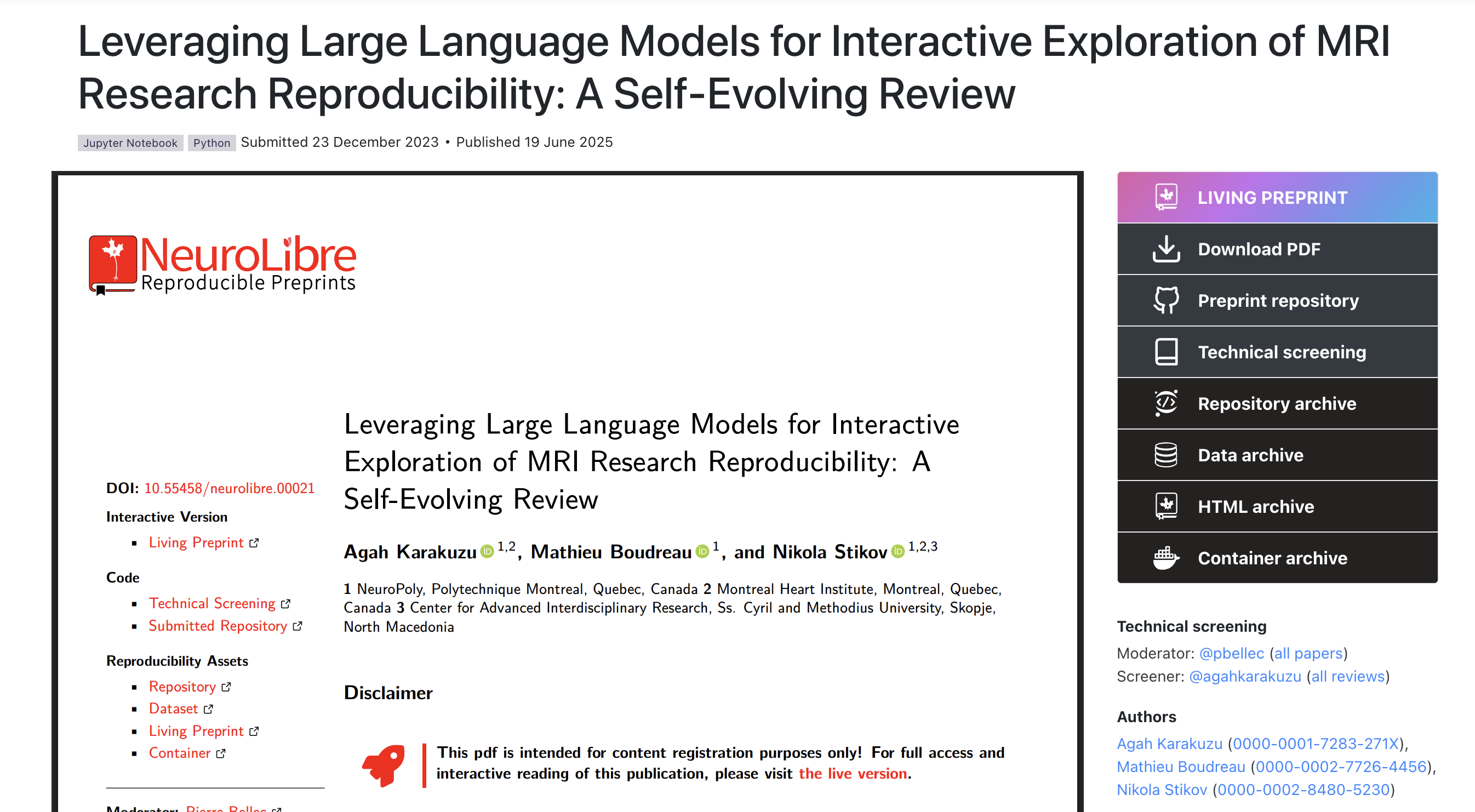

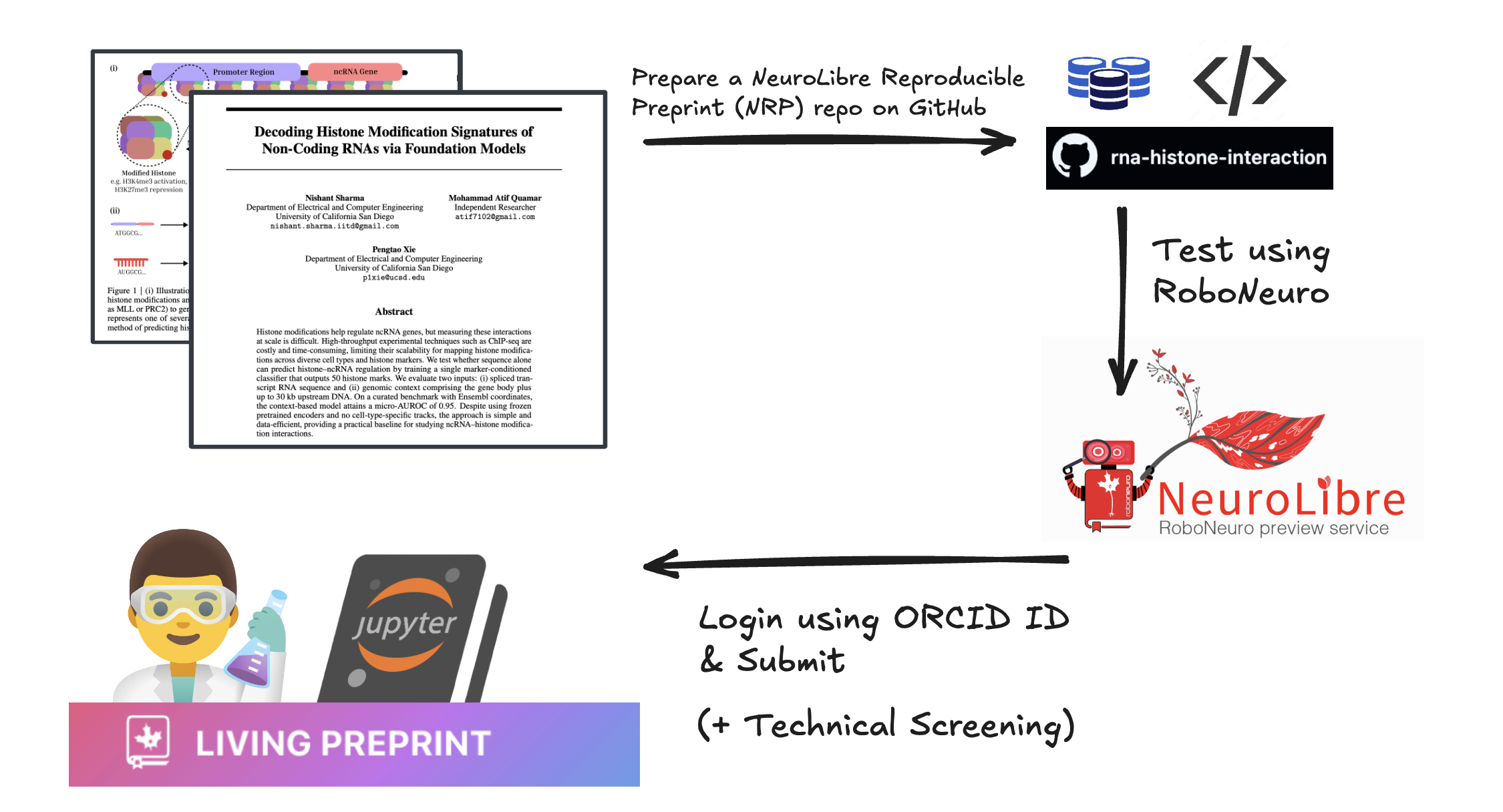

What you see in this image is a living preprint. It looks like a paper, but it behaves like a runnable project. If you’re learning, you can it like a guided lab with jupyter books. If you’re reviewing, you can check claims easily without becoming tech support, because the publishing process has these checks built-in. If you’re building on top, you have all the resources you need here.

NeuroLibre is a preprint publishing platform for reproducible, executable research objects. Instead of treating the PDF or the TeX file as the main artifact, a NeuroLibre publication packages the paper with the its code, data, and a defined runtime so the work can be executed from a web browser. NeuroLibre describes these as “reproducible publications” and supports Jupyter notebooks that can be render as a living, interactive preprint.

A useful way to frame the real value of this platform is provenance. Instead of treating plots as just infographic images, the paper exposes where they come from and how they were produced. The goal is that results are traceable back to data and code, and executable end to end in the same environment thath the authors originally used.

NeuroLibre’s review process is primarily technical. Its mainly concerned on whether the resource builds and runs, and whether the reproducibility assets are present and usable, not on judging scientific novelty. NeuroLibre automates the build and reproducibility checks, but humans moderate submissions and run a technical screening process before anything is published.

Illustration of the whole process of putting your article on the platform.

Illustration of the whole process of putting your article on the platform.

“If only research outputs were more machine interpretable, searchable and discoverable then research could be incrementally automated and progress would go through the roof.” This is one of my favorite lines from the article The Business of Extracting Knowledge from Academic Publications. The spirit of NeuroLibre is an embodiment of this idea. If we can make publishing on an open platform like fully frictionless for authors, we get much closer to truly complete papers.

My position and all views, at the time of writing, come from the POV of a beginner in ML research. All views are my own and do not reflect the ideology of my affiliates.

Thanks to Dr. Nikola Stikov for motivating me to write this blog. I had the chance to speak with him and share his unconventional, potentially world-changing vision with you.

Bib

- Andrej Karpathy. A Survival Guide to a PhD

- ICLR 2026 Program Chairs. ICLR 2026 Response to Security Incident. ICLR Blog (Dec 3, 2025)

- ReScience C. FAQ: replication vs reproduction

- alphaXiv. Explore

- Distill. Distill: Latest articles about machine learning

- Journal of Machine Learning Research (JMLR) (website)

- Markus Strasser. The Business of Extracting Knowledge from Academic Publications

- Hacker News discussion page for The Business of Extracting Knowledge from Academic Publications

- NeuroLibre. project site

- Agah Karakuzu. Toward a woven literature: Open-source infrastructure for reproducible publishing. NeuroLibre (DOI: 10.55458/neurolibre.00041)

- ChatGPT and Galactica are taking scientific papers to their logical conclusion.

- Interview. Nikola Stikov on Open Science inspiration

- Does Peer Review Penalize Scientific Risk Taking? MIT Sloan Review